In the second half of the 19th century, Sulina, one of the Danube Delta’s branches, became a hub of transnational engineering aiming to transform this perilous section of the Danube into a fully navigable waterway. Complicated hydraulic works became successful under the coordination of British civil engineer Charles Hartley. In today’s blogpost, Romanian historian Prof. Constantin Ardeleanu provides us with insight into one of the many facets of the complex activities of the European Commission of the Danube, one of the world’s earliest international organisations, focusing on one of its most influential technocrats, Charles Hartley.

***

A European celebration

On September 3, 1861, the small town of Sulina hosted a rather strange festivity: the European Commission of the Danube, an international organization established through the 1856 Paris Peace Treaty, celebrated the festive opening of its hydraulic works which aimed at regulating navigation along the Lower Danube. Almost two hundred guests from Istanbul, Vienna, Odessa or Bucharest arrived to celebrate this European success, which was presented in journals from around the world.

For some participants, the celebration marked the symbolic conclusion of the commission’s main task; for others, it was just the beginning of much more complex hydraulic works.

There were many actors which deserved the organizers’ gratitude: the seven commissioners, their governments, dozens of bureaucrats and technocrats in the organization, the government of Romania as host state for the organization’s headquarters, Danubian consuls and bankers, naval officers stationed at Sulina, merchants and ship-owners who were the commission’s main beneficiaries, but also the tax payers for these hydraulic works.

Free trade and hydraulic works

Economic rationality and the belief that free trade was a core principle of European civilization that would bring prosperity and peace across the continent dominated the participants’ speeches. The same spirit had stood at the basis of the Danube Commission. The victors of the Crimean War had defeated not only the Russian armies, but also its protectionist tendencies, and the Black Sea periphery was open to capitalist investments. The commission was an emanation of Europe’s Concert of Powers, which embarked on a cooperative project aiming to remove the natural and artificial obstacles that had made Danube shipping insecure and costly. In line with similar humanitarian interventions in unsettled parts of the Ottoman Empire, this was a ‘technocratic intervention’ into a backwater of the Ottoman Empire, which Europe had to secure for larger international commercial interests, for continental prosperity and peace.

As this blog aims to show, the Danube Commission managed to remove insecurity along the Maritime Danube by correcting the river and providing it with proper navigational institutions. But it also contributed to the creation and dissemination of knowledge and to the formation of a network of hydraulic professionals. Such knowledge and networks spread to waterways around the globe, thus linking the Danube to some of the most daring technical projects of late 19th century. As I will further show through several examples, technocrats loosely organised in epistemic communities started to be included in political decision-making and the governance of strategic transnational initiatives related to building infrastructure in colonial areas. The early success of the Danube Commission was a great incentive for further international technical cooperation in, for instance, the Suez or Panama canals.

The road to success

Charles Hartley was the hero of the Sulina festivities. When he had joined the Danube Commission in 1856, at the age of 31, he was an experienced civil engineer. He had been involved in the construction of railways in Scotland and in the modernization of the harbour of Plymouth. He was invited to become the commission’s engineer-in-chief after serving in the Crimean War in a corps of British engineers.

Five years later, after the success of the Sulina works, Hartley was decorated by several European monarchs and was honoured in Britain with a knighthood, a distinction rarely awarded to engineers. Consecration among his peers came after having presented, in March 1862, a paper on the Sulina works at the Institution of Civil Engineers in London, the world’s most prestigious professional body of engineering experts, which awarded him several distinctions. The question is why were his hydraulic works so revolutionary?

Data collection and knowledge production

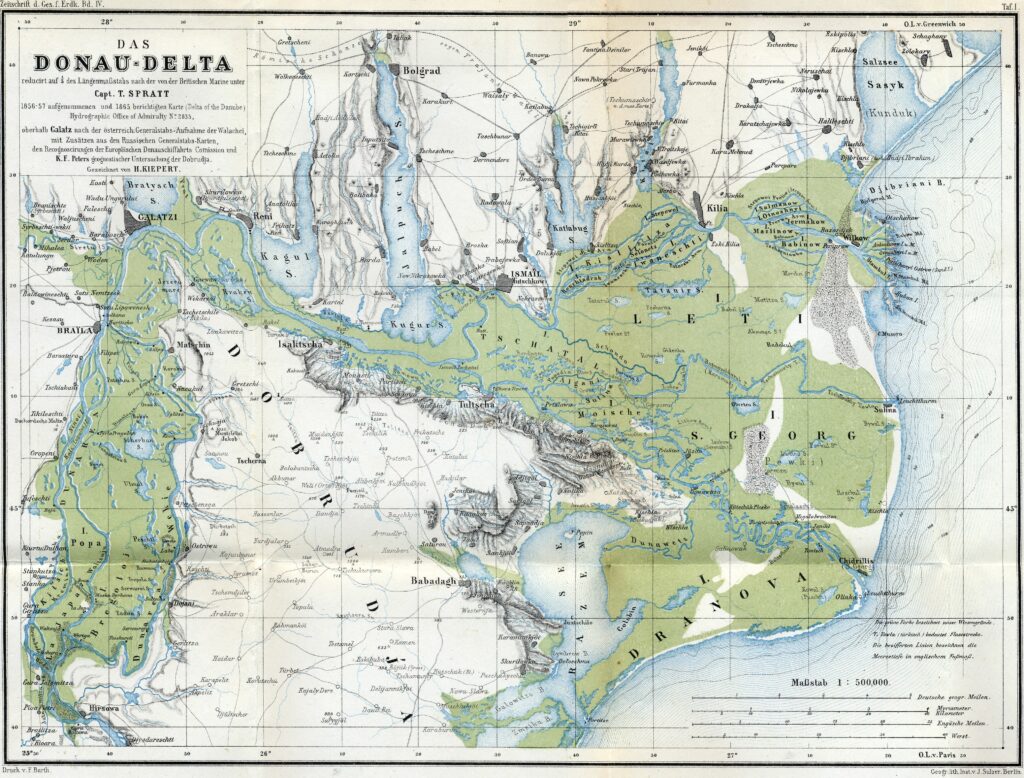

Hartley built two parallel piers at Sulina in about three years, one of fourteen hundred meters, the other of nine hundred meters. The technical vision was his own, while the location of Sulina was imposed by the seven commissioners.

Before 1856, the hydrography of the Maritime Danube was largely unknown. The Russians had done a scientific survey of the Delta in the 1830s, but proper maps and bathymetric recordings lacked. Hartley needed to acquaint himself with the variable local geography and hydrography before proposing which of the three main branches of the Danube was best fit for improvement. Studying the river with its seasonal floods, predominant currents and winds was part of a long transnational process of data collection and knowledge production in which Hartley was supported by professional English and Prussian surveyors. Hartley would have wanted more time for understanding the large variations of depths, flows, winds, currents and tides, but commissioners forced him to move as quickly as possible.

In October 1857 he presented his Report, a very detailed scientific piece of the natural factors that obstructed river navigation. In the second part he laid out technical solutions for improving either the St. George or the Sulina mouth. He would have preferred the former, which was however the more expensive and lengthier option.

Technical and diplomatic disputes

But few hydraulic experts agreed to him at the time. After the Crimean War, engineers from around Europe provided technical advice to their governments or referred to the best solution for improving the Danube. Prestigious engineers, hydrographers and seamen from Britain, France, Austria, Prussia or Sardinia provided advisory opinions. Eduard Nobiling, the Prussian engineer-in-chief for the Rhine at Coblenz, drafted in 1857 no less than six memoranda on Danube’s morphology and provided complex improvement plans. There was hardly anything similar in all these well-intended proposals. The commissioners themselves agreed to disagree, and by 1858 the Danube Commission was deadlocked on its next moves. European governments were alarmed with their delegates’ indecision and four states, Britain, France, Prussia, and Sardinia, sent engineers to an International Technical Commission, a proto-epistemic community or an example of ‘science diplomacy’ that convened at Paris in 1858. Four engineers agreed to Hartley about the choice of the mouth, St. George, but they favoured a completely different solution: river locks instead of parallel piers.

Meanwhile, commissioners had directed Hartley to start provisional works at Sulina, under pressure from the local mercantile community which expected results from Europe’s intervention. Expertise from other rivers was used in the planning and actual constructions from Sulina. Hartley and his assistants visited hydraulic projects on the Vistula, the Elbe and the Rhone, and they received maps and detailed plans of the works conducted by national governments on several other European rivers.

Building in the periphery

At the same time, Hartley set up the logistics of procuring and transporting construction materials, stone and timber, and for gathering much needed human resources. Mechanical tools were purchased by the commission’s agents in Istanbul, Budapest, Vienna and London, while the works were carried out, under the supervision of British and Prussian foremen, by Moldavian, Turkish, and Bulgarian workers.

The fruits of success ripened with the extension of the piers Hartley was busily erecting at Sulina, and from a depth of below nine feet in 1856 at least fifteen feet were maintained throughout 1861. This marked the beginnings of a technical success that completely transformed Hartley’s life and career.

Around the globe

Since the early 1860s, Hartley was invited as a consultant for improvement works on rivers, ports and canals around the world. He was employed in fluvial and maritime engineering works on four continents: on rivers such as Dnieper, Don, Hooghly, Mississippi, Scheldt, on the Suez Canal, in ports such as Trieste, Burgas and Varna, Constanța, Odessa and Durban. He had a constant interest in and got involved with some of the most daring 19th century projects of international waterways, such as the construction and development of the Suez and Panama canals. Eventually, after Great Britain took control of the Suez Canal Company, Hartley became a member of its Technical Committee, a position he kept for almost 25 years.

Sulina as an engineering hub

Hartley travelled extensively during the 1860s, but his home base remained at Sulina. Thanks to his engineering, Sulina became a must-see destination for civil engineers doing hydrotechnical works. In 1864, Hugh Leonard, a British civil engineer in charge with the works on the Hooghly River in West Bengal, visited Europe for research. He came to the Danube and asked for Hartley’s opinion on the improvement of the Indian river. Leonard further headed to the Po, Vistula, Rhine, Adour, Tyne, Wear, Tees, Clyde, Severn, Ribble, and his reports prove that there was a tight community of river experts aware of the hydraulic works carried around the world and that Hartley was a respected authority in the field of river and harbour works.

Since the 1870s Hartley remained consulting engineer of the Danube Commission, and was assisted by a resident engineer. The position was given to a Danish engineer Karl Leopold Kuhl, followed by another Dane, Eugene Magnussen. Both worked under Hartley’s supervision and continued to present the results of their works to international audiences. This made the Danube Delta one of the best-documented example, then and now, in understanding the evolution of deltaic systems.

Conclusions

In early 20th century, Hartley was an accomplished engineer. Perhaps the best recognition of his talents was the ‘Albert Medal’ which he received in 1903, in the same decade as Alexander Graham Bell, Andrew Noble or Marie Curie, for his works at the Danube and the Suez.

Back at Sulina, Hartley was acclaimed as the ‘Father of the Danube’, and regarded as a technical genius who had managed to ‘civilise and discipline nature.’ As Romania’s Prime Minister Dimitrie Sturdza stated, the improvement of navigation along the Maritime Danube was ‘a veritable triumph of peaceful international work, conceived with the support of science and conducted with constancy, assurance and loyalty.’ Hartley epitomised all these qualities, and his professional reputation contributed tremendously to the success of the Danube Commission as a whole.

Rationalising nature, governing and managing it for maximising economic benefits is a feature of the long 19th century. States did it on their territories in large infrastructural projects meant to boost transportation networks or to develop local economic resources. But this happened also at a sub and supra state level, in which early international organizations were directly involved. Engineers were vital in all these projects, and they started to assemble themselves in national and transnational professional associations. It is remarkable how well connected these epistemic communities were and how fast technical knowledge circulated. As the source of prosperity and peace, economic rationality was well guarded by thick walls of dykes and embankments, busily constructed by engineers, a veritable new model army deployable around the globe.

***

We want to thank Constantin Ardeleanu for this fascinating overview of his work on the European Commission of the Danube and we are looking forward to hear more about it in the future. For more information on the Commission, see Constantin’s book: The European Commission of the Danube, 1856–1948. An Experiment in International Administration, Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2020.

Last edit: 16 March 2023